- Home

- Gerry Spoors

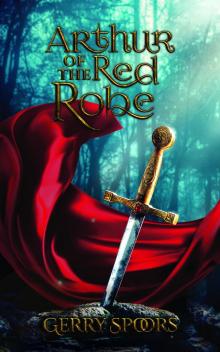

Arthur of the Red Robe Page 8

Arthur of the Red Robe Read online

Page 8

"At first the family kingdoms remained stable, because Cunedda, and Ambrosius—who ruled in the West—had set up a ‘Council of Nation Kings’. They were able to maintain the systems of law and order that the Romans had instituted. But then came invaders from the Sea of Man who plundered the land of the people of the Western Shore and carried away their women. It was to Cunedda that our friends turned as none could match his bravery and wisdom.

“Thinking that all was well with the Picts, with whom we had lived at peace for many years, Cunedda set off for the Western Mountains with some of his sons and warriors to support our allies. Only two of his six sons were left behind—Germanianus, my father, (also known as Arthur?), and Leodonus. Leodonus was overlord of the Northern Votadini and my father overlord of the Southern families.”

***

“Bloody hell, Pam, did you really say Arthur? It couldn’t be, could it? Crikey! What have we discovered?” Gerry was so excited at the prospect of this being the first true historic record of King Arthur.

Pam calmed him down a bit by saying that the name ‘Arthur’ might also have been used by Cunedda as it really means The Bear and others might have used the name at around that time. The original was a bit vague, but it was definitely pointing to the name Arthur.

Gerry agreed as he’d read that Arthur has also been thought to be a title rather than an actual personal name. Many had thought that it actually meant ‘The Bear’ but this new revelation seemed to indicate that it was a real name. She had to concede this and was beginning to think that Gerry really did know quite a bit about this period of time.

“Pam, do you agree that the so-called Dark Ages were not completely dark?” Gerry was asking this even though he was well-read on the subject, but Pam’s reply quite surprised him.

“I think a lot of the history of the British people who lived here before the Anglo-Saxons was supressed by those of the Roman Christian tradition. Bede, in particular, who lived in a monastery which complied with Roman rules, hardly ever mentions the British Christians as they followed the earlier Irish and Ionan approach. He must have had so much information, as the library at Jarrow was thought to be quite extensive. Now whether these records were destroyed earlier or he just chose to ignore them will never be known, but it seems that the Anglian Christians hated the British ones. It seems that the mutual hatred between different Christian traditions, which still exists—particularly in Ireland—goes back almost to the beginning of the Christian religion.”

“That disappoints me so much,” said Gerry. “I’ve always thought of Bede as a great historian who had written a definitive history of Britain, but it seems that it was only a partial account. Although I suppose he was restricted by his ecclesiastical bosses, not to mention the rulers of what I suppose was Bernicia at the time.”

“You really do know quite a bit about the time, don’t you, Gerry?”

“Well, only what I have gleaned from library books, but I have been researching for some years!”

Chapter 4

“Of course, you know what that means,” said Wilkinson to Gerry and Pam.

“Well, I suppose it means that we’ve got ourselves a very significant historical record,” came the reply from Gerry.

“The real significance is that this is apparently one of the few, if not the only, original account of the history of Britain in the Dark Ages. All other so-called histories were written after that time—sometimes hundreds of years later—recounting stories passed on from generation to generation, by rumour and oral tradition, as tribal sagas. And this is the earliest mention of Arthur—can you believe it?”

“The main records we have are: ‘Historia Brittonium’ by Nennius, completed around 830; ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People’ written by Bede in around 731; ‘On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain’ by Gildas, written in the mid-sixth century; ‘Gesta Regum Anglorum’ written by William of Malmesbury in about 1125; the ‘Annales Cambriae’ completed in the 950s; the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, the earliest parts of which were written over the period 871–899; and ’Y Gododdin’ a poem by Aneurin, written in North Britain in the sixth century,” said Wilkinson, hardly stopping for breath.

He continued: “Many of the later accounts embellished, embroidered and simply distorted the basic facts. And that’s how the story of Arthur came to be the fairy tale that we know today. There are so few details about the early British tribes and their relationship with each other and with the Romans. There is even less information about the changes that occurred when the ‘Anglo-Saxons’ started migrating to this island.” “So this could really change all of our ideas about our ancestors?” asked Gerry.

“That’s an understatement, to say the least,” Pam chipped in.

“You’re absolutely right,” said Wilkinson, who was finding it harder and harder to subdue his excitement. “I would say that we are on the brink of learning the truth about the most traumatic period in Britain’s history. We could learn the truth about Arthur, about what happened to the early British tribes, and whether they were subjected to ‘genetic cleansing’—as we call it now—by Anglo-Saxons.”

“Yeah, I just can’t wait to hear the rest of the story. It’s so exciting just to think what might lie ahead of us, and what secrets we will be privileged to read at first hand,” said Gerry. “So let’s get on with the translation!” said Wilkinson. “We’ve had enough chatting. Let’s go!”

At that moment, Jeannie rushed in shouting: “It’s in the paper!”

“What’s in the paper?” said the trio, all together.

“About the jars!” came her reply.

“WHAT!”

“That bloody Truelove!” shouted Wilko. “I knew he would do something like this. Let me have a look.”

Jeannie handed over a copy of the ‘Evening Chronicle’ which was Newcastle’s evening paper. Thankfully, it wasn’t on the front page and only occupied a couple of column inches on Page 7. All it said was that a University spokesman had revealed that an intact, stoppered jar from Roman times had been discovered locally, and was currently undergoing investigation at the University. The spokesman said that Dr Wilkinson Wilson was leading the investigation, in close cooperation with Dr Jeannie Richards.

At that moment, the lab phone rang and Jeannie answered it. It was someone from the BBC’s Look North programme, asking questions about the article in the paper. Jeannie said that they really needed to talk to Dr Wilkinson so she passed the phone to him. Wilko was very diplomatic and said that there was nothing significant to report and that once the investigation was complete, he would be happy to give a full account. The reporter didn’t seem to want to let it go at that and it was obvious that Wilko was now becoming a little irritated. Finally, Wilko said he was in the middle of an important analytical procedure and the conversation ended.

Wilko was fuming and felt that the BBC would not be letting it go at that. He suspected that they would be turning up at the department, sniffing around.

“Don’t worry, I’ll sort it out!” said Jeannie.

“How on earth can you do that?” asked Wilko.

“My boyfriend is a senior manager at the BBC. I’ll make sure he puts pressure on them or else I’ll withdraw his comforts, shall we say, and if that doesn’t work, I’ll tell his wife about us.”

At that moment, you could hear a pin drop. No one knew what to say. Jeannie broke the silence by saying: “I’m going to phone him from my office,” and left the room.

All present just looked at each other in amazement. Wilko was the first one to break the silence: “A few years ago, my wife and I were walking our dog near to a copse, which we didn’t realise contained pheasant pens. As we were walking away, the farmer came storming across the field towards us in a Land-rover and was absolutely furious. He said that he was absolutely ‘agasp’ at us and other local villagers just walking across his fields. Presumably, he meant to say ‘aghast’ but he repeated ‘agasp’ twice more. To be honest, I am now agasp to disc

over that Jeannie has a boyfriend, and he’s a married man.”

Once they’d pulled themselves together, and Jeannie had returned with a smile on her face, the group got down to their work again.

Chapter 5

"My grandfather, Cunedda, wasn’t married when he became King of our nation at the age of 21. And as the life of a ruler can suddenly be cut short, he needed sons to support him and carry on the dynasty. He had heard of a great beauty who was the daughter of Coel Hen, King of the Selgovae, and his wife Stradwawl. Her name was Gwawl, and he decided to seek her hand in marriage.

"When he first saw her as a 15-year-old, the breath was stolen from his body, and he couldn’t control his emotions. They were married within weeks of meeting and he took her to his northern home at Traprain. Only eight months later, a son was born to them named Typiana, but he was a weak child and the harsh climate of Traprain didn’t help. He died after a few weeks and there was much grief in the Royal Township.

"Cunedda decided to switch his township to his southern home at Gefrin, beside the River Glein, which had a much milder climate. He had become depressed with the thought that Gwawl might not be able to bear more children. But his fears were unfounded and in total, she bore him six more sons and two daughters. His sons were Osmail, Rumaun, Dunant, Ceretic, Leodonus and Germanianus (known as Arthurus, the Bear).

"Cunedda and Gwawl were a kind and loving couple who were well respected throughout their own nation and throughout the island of Britain. When Cunedda’s own brother… died young, they took his sons Abloyc, Docmail and Etern as their own, and did not discriminate between any of their children.

"They lived happily at Gefrin for many years, although in the summer months they spent some time at Traprain to ensure that the people of the Northern Kingdom did not feel neglected. Eventually, Cunedda decided that it would be best to appoint his son Leodonus Lord of the Northern Kingdom.

"Life was not so easy for our brethren in Venodotia (the area now known as Gwynedd and Powys) in the west, as there were constant invasions by the Scotti, who came from across the Sea of Man in Hibernia. Land had been stolen from them, particularly in the area known as Lleyn. They were not content with just taking land but also helped themselves to the animals and women of our brothers. It was a serious situation, because even though this was happening in a relatively small part of Venedotia, the numbers of Scotti were increasing as they found how easy it was against the Venedotian king, Ambrosius, and his people. The Venedotians had never needed to make war before, having always been under Roman protection. It was feared that eventually, the Scotti might become so powerful that they could threaten other British kingdoms.

"Although Ambrosius was the most powerful of the Western Kings, he still couldn’t raise sufficient forces to fight back the tide of Scotti. He sought help from Wortigernos, who was then the most powerful of the Southern British Kings. But Wortigernos was faced with strife in his own kingdom and was worried that if he sent help it might weaken his own position. Realising that the infiltration of Scotti threatened not only Venedotia but also the whole of the island of Britain, Ambrosius decided to ask Cunedda to help him in his hour of need to beat back the invaders.

"Cunedda called a Royal Council at Gefrin, and it was decided that he would lead a war band over the mountains to Gwynedd to help Ambrosius. The latter had offered the Votadini new territory within his lands if they could beat off the Scotti. Cunedda and Gwawl would leave with four sons and one daughter, as their other sons were already responsible for running the two parts of the Votadini Lands. Their eldest daughter had entered the monastery at Birdoswald where she had become acquainted with Patrick Morn.

"Cunedda had several reasons for wanting to go. Obviously, it was essential to drive out the Scotti for the reasons previously stated. But he was still ambitious and here was an opportunity to expand the lands of the Votadini, without being aggressive to his neighbours. He was also quite flattered to be become a sort of ‘saviour’ to the Venedotian people—and to the once great Ambrosius.

"Over the next few years, Cunedda lived up to his reputation and effectively repelled further Scotti invasions. However, being a man of great wisdom, he did not force those who had already settled to leave their homes. Eventually, they integrated with the Venedotian people and lived on peaceful terms.

"The Scotti did not completely stop their attacks on the island of Britain. They switched their interest to the lands of the North and particularly to the lands of the Damnonii. They had much success and eventually founded the Scottish kingdom of Dal Riada. It was whilst preaching amongst the Damnonii that Gwawl’s friend Patrick Morn was captured by the Scotti and taken to Hibernia. Here, he proved to be so astute that he was able to win the hearts of the people and to convert them to Christianity.

"Back in the Northern Votadini lands, there was little or no threat from the North, partly because these people were not particularly organised into kingdoms, and partly because of the reputation of the Votadini as fighters. This ability had been bolstered during Roman times and afterwards by the migration—to Bryneich at least—of Angli from across the sea in Angeln. They had come first as mercenary soldiers to join the Roman Army, but later migrants brought their families with them.

“The Angli brought many useful skills such as agriculture, metalworking and seamanship. They were also excellent warriors and knew how to organise defences against attacks from both land and sea. After the Romans had left, the Votadini kings had been happy for the Angli to settle in various places along the coast of Bryneich, as they were very much people of the sea. Cunedda had welcomed them because he knew that previous immigrants from Angeln and Frisia had not caused trouble with his people and had looked after their land and animals well. They were extremely efficient farmers and had boosted the yield of crops on the small areas of land they had been given.”

Chapter 6

"When the call had come for him to go and defend the land of Gwynedd, Cunedda had been content to leave because he knew that his sons Leodonus and Germanianus Arthurus were more than capable of looking after the Votadini lands. Germanianus, who was in charge of the Southern Lands, continued to live at Gefrin for a short while—that is, until the Anglian Uprising occurred. Leodonus was not as clever or as powerful a warrior as Germanianus but Cunedda knew that Germanianus would support his brother whenever required.

"Germanianus (Arthurus—the Bear) was only nineteen years of age when Cunedda went to Gwynedd in 479. His priority was to know the people of Bryneich and particularly those south of Hadrian’s Wall. This area had been neglected, as it had acted as a kind of buttress between Bryneich and the lands of the Brigantes. Germanianus wanted to improve the lot of the Votadinian people, but this wasn’t purely for their own sake. He had studied the Latin histories of the Roman Caesars, who were his idols. He had learnt that subjects were far more likely to lend support in times of trouble if they had been looked after, and if they had more to lose.

"It was during one of his trips to the land of the Three Rivers (Tyne, Wear and Tees?) that he met a beautiful young woman called Gwynyfawr. She was the daughter of Ennian, who farmed land on the south bank of the River (Wear?) Here, on a wooded slope lay the settlement of Penchion, which was well defended in case of incursions by the Brigantes. Ennian was Chief of the village, and his people had lived there for several centuries under Roman rule.

"Ennian had known that Gwynyfawr was very special from an early age. She stood out not only for her good looks, but she was also exceptionally clever and very determined. Not for her the drudgery of being a farmer’s wife, with children running wild all day. Only a prince would do for her. ‘A prince? How on earth are you going to find a prince?’ was a regular question from her mother and father, her sisters and brother. They would tease her, although secretly some of them thought that it might indeed happen, as she was so beautiful. Then one day he just walked through the gate of the village and straight to her house!

"He had no idea that he would me

et his future princess on that beautiful spring morning. He was riding around the area with his men, just meeting householders and assuring them that he would provide safety for them. Cunedda had continued the system of having a network of local officials, who would pull together local defences when danger threatened. They would also organise the sending of messengers to the King should additional support be required. Each official had a part-time band of helpers, who would be there to persuade reluctant men to hand over their dues.

"When danger did arise, each householder would provide a contribution in terms of manpower—should he or his sons be able—and food supplies for the King’s war-band if it was needed in his area. Each household was also required to contribute an annual offering to the King, depending on status and means. The inhabitants of the Royal Townships had to contribute the most, but in return had certain privileges, including occasional invitations to Royal gatherings and festivities.

"Gwynyfawr was helping her father in the fields when a handsome young man, with an obvious royal bearing, came riding on horseback across her father’s land. She had no idea who he was, but Ennian, although he’d never seen him before, knew immediately he was Cunedda’s son, Germanianus. He dropped his tools, which startled Gwynyfawr, and ran towards the visitors. His daughter was shocked as she thought that the men might be enemies, or had come to collect a debt. And when she did discover who they were, she thought they might have come to ask Ennian and his men to go away to fight for the King.

"Imagine her embarrassment when she found out who the man was who was being invited as a guest into their house, to share their food. She gasped when she was told it was Germanianus, as she had heard of the handsome prince with red-gold hair. In fact, on many a night, she had gone to sleep with visions of the young prince in her mind’s eye.

Arthur of the Red Robe

Arthur of the Red Robe